Corey Bailey

Audio Engineering

USEFUL INFORMATION

ANALOG TAPE: DO IT YOURSELF?

60 years ago or so, it was easy to spot a die-hard audiophile because he or she

owned a reel-to-reel tape recorder. I was one of them. I owned an early

production-model Roberts, which was considered to be one of the serious

audiophile decks of its day. Although the manufacturers tried to make home

recorders as simple as possible, the whole process had a rather steep learning

curve. It’s even steeper today.

Record collecting can be relatively simple, particularly if a person sticks to vinyl

LP’s (which, will make the selection of a record turntable and styli a lot simpler).

However, one can purchase a single turntable which will play all speeds and sizes

of records.

Reel-to-reel tape recorders are mostly format-specific. Tapes recorded on different

format recorders are generally not interchangeable.

When the business was active, in order to be able to play 98 percent of the ¼” tape

formats that were used, I owned (and had to maintain), at least, four tape decks.

This brings up the maintenance issue: Tape recorders are very complicated electro-

mechanical pieces of equipment for which very few (if any) parts are still available.

This also means acquiring the proper test equipment and learning how to use it or

finding a good repair technician.

If you want to try this yourself at the hobby level, the most difficult task will be

finding an affordable, working reel-to-reel tape recorder to get started with. There

are some talented technicians that specialize in restoring old professional tape

decks for archival purposes. As you might imagine, those refurbished tape decks

cost professional prices. The alternatives are consumer and ‘Prosumer’ reel-to-reel

tape decks. Some have been expertly refurbished and good used ones can still be

found.

For those who are new to analog audio tape recording, here is a link to a student

primer provided by the University of California, Santa Cruz titled: Analog Tape

Recorders. Check out the Analog Tape page in my glossaries section for some

simple definitions and descriptions. Also visit my Links page. Some of the sites

there have volumes of information about playing and archiving audio tape.

You will need to learn how to identify the various formats, adjust parameters such

as azimuth, and be able to get the best out of decaying tapes that have been

improperly stored for years. I’m not intentionally trying to discourage you from

becoming a collector of audio tapes, I’m simply telling it like it is and suggesting that

you do some extensive research before jumping into a hobby that can easily turn

into a money pit.

One of the most popular uses for home reel-to-reel recorders was to make song

tapes of favorite songs from records or off-air, often known as ‘mix tapes’.

I made a few myself way back when. This is the vast majority of what you are going

to come across at garage sales and swap meets. Some are OK, some are poorly

made. Of course, a lot of family history was recorded on reel-to-reel tapes and this

is what you may find in Grandma's attic. On the other hand, there were quite a few

commercial recordings made for reel-to-reel enthusiasts, and some still survive.

Some are very collectible.

Acetate base tape

The vast majority of family history recordings on reel-to-reel tapes that I have

archived were made from the 1950’s through the 1960’s. This was the era of

acetate tapes that are now very brittle and delicate. This type of tape is prone to

breaking and leaving jagged ends that are difficult, if not impossible, to repair.

Acetate tape can be identified by

holding the reel up to a bright light.

If you can see light through the reel,

it’s most likely acetate because the

acetate base is clear.

Fig. 1 is a 7” reel of acetate tape

being held up to a 40 watt light.

The light transmission is obvious.

Polyester tape, (Fig 2.) when held up to

light, is opaque.

(The light on the surface of the reel is the

camera flash.)

The caveat here is that if the acetate tape in question is suffering from a deformity

called ‘cupping,’ it may not pass light edgewise as well as shown in the example.

Cupping is when the edges of the tape curl up somewhat, making the tape resistant

to wrapping on a reel. The tape itself looks like the shape of a metal Venetian blind.

Cupping results from the tape losing moisture over time. If severe enough, cupping

can cause the oxide to fall off the backing. You will usually notice the oxide flaking

condition on the outer wraps of the reel. While making acetate tape easier to

identify because the clear base is now identifiable, flaking is non-reversible. If any

of the recording has separated from the base, it’s gone forever, turned into a small

pile of oxide flakes. If the Cupping condition is not severe, there is a possible

treatment that can be done called a ‘B-Wind’ whereby the tape is wound onto a

take-up reel with the oxide out. The reel of tape is stored for a period of time to

possibly reverse the condition.

Acetate tape that has become too brittle to be playable can sometimes be re-

hydrated. The short story is that acetate tape usually can be re-hydrated if left in a

moist environment. This can be as simple as placing some dampened (not wet)

cotton balls in the corners of the tape box with the tape for 24 hours or so, or as

complex as making up a system which suspends the tape over distilled water in a

closed environment and left for a period of time. The key is to not have the tape

come in contact with the source of the moisture. I have written a separate article on

this subject which goes into more detail: Moisturizing Acetate Tape. If you have old

tape you suspect is brittle acetate, consult a professional or do some research

before attempting anything. The information is out there.

Polyester base tape

Polyester base audio tape first appeared on the market in the early 1950’s, and, by

the late 1960’s, it had basically replaced acetate base tape. Polyester base audio

tape was readily embraced by the professional audio community because the

improved oxide formulations allowed for increased dynamic range. Unfortunately,

during the mid 1970’s, many manufacturers changed their oxide formulation (mainly

the binder and lubrication chemistry), and things started to go bad from there.

Some of those newer tape formulations had severe oxide shedding problems.

As it turns out, that was an indication of things to come in later years.

A surprisingly large percentage of polyester tape that was made in the last 40 years

or so, suffers from a condition known as binder hydrolysis. This is a condition

whereby the binder (used to adhere the oxide formulation to the polyester base)

has absorbed moisture over time, causing the oxide to become soft and sticky and

leave oxide deposits on all of the stationary tape recorder parts (Guides, Heads,

Tape Lifters, etc.). Quite often, the tape will chatter across the tape heads as the

result of a condition known as sticky-shed syndrome.

Ampex Corporation, one of the manufacturers plagued by the reformulation

problems, came up with the solution of ‘baking’ audio tapes at 130 degrees

Fahrenheit for 12 to 24 hours, depending on the size of the reel and the thickness

of the tape. Much has been written about this process, and the research continues.

Baking is a temporary solution because after a week or so at room temperature, the

problem tapes will return to their sticky state. Experience has shown that polyester

tape can be baked more than once. The possibility of adverse affects resulting from

audio tape baking is still being debated.

I discuss the baking process in a separate article.

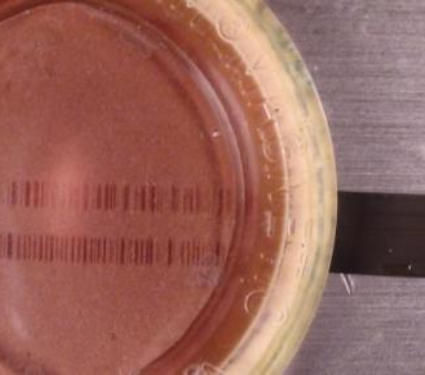

Identifying the track format

One of the simplest ways to

identify the track format of a

recorded tape is to view it with a

magnetic viewer. This is a gadget

that has extremely fine magnetic

particles suspended in a fluid.

When placed over a recorded tape,

the magnetic viewer shows the

actual magnetic recording and

reveals the track format….almost.

Here are two pictures of recorded

tapes revealing their format under

a magnetic viewer:

Fig. 3 (Right) is a 2 track stereo

recording. However, it could be a

half-track mono (recorded both

directions), since the two formats

share almost the same track width

and placement (0.01” difference).

If the tape is a half-track mono, one

channel will play forward and one

channel will will play backwards,

when played on a 2 track machine.

Quarter track can be recorded in both directions. If that is the case, you will see

four bands of magnetism. It could also be a four channel recording which, shares

the same quarter track widths and spacing. At least, by viewing the tape with a

magnetic viewer, you can tell which play head to use for continuing the

investigation.

If the quarter track tape shows four bands of magnetism, you will have to play it one

direction and then turn it over and check the other direction on a quarter track tape

deck. If the tape plays correctly in both directions, it’s a quarter track recorded in

both directions. If any the channels play backwards, in either direction, you’ve

probably got a four channel tape on your hands and will need a four channel tape

deck to play it. A quarter track tape recorded in both directions (most likely stereo),

played on a 4 channel tape deck will play both forwards and backwards at the

same time. Likewise, a quarter track tape recorded in both directions and played on

a 2 track tape deck will play both forwards and backwards at the same time with

one channel being lower in level if your machine is calibrated correctly.

Tape Thickness

Audio tape thickness is basically determined by the material used as the base.

The actual measurement is of the overall thickness. The oxide and the back coating

(if used) are very thin. The measurement itself is in one-thousandths of an inch and

is expressed in mils. All acetate back tape is 1-½ mils thick.

All professional tape is 1-½ mils thick. Polyester backed tape comes in three

thickness; 1-½ mil (also expressed as 1.5 mil), 1 mil and ½ mil which, is often

expressed as .5 mil. The thinner tapes may give a better head wrap and longer

recording time, but that’s about it. The downside of using a thinner tape is that there

is more of the possibility of crosstalk between the layers. Particularly, if the tape

does not have a back coating.

Lubricating audio tape

I will lubricate a tape suffering from binder hydrolysis or sticky shed syndrome first

because I consider baking to be a last resort. I have found that the method and

product that I use for lubricating polyester base audio tape to be about 90%

effective. If the oxide appears to be sticky or shedding during the lubricating

process, resists you in any way, stop and read my articles on baking or lubricating

audio tape to possibly determine if you should proceed. There are several

approaches, using a number of products and chemicals currently in use to lubricate

audio tapes. I use a lubricant specifically formulated for audio tape manufactured

by LAST Factory. Check out their website. They make products for records and

tapes along with information on how to use them.

I often have to use more lubricant on problem tapes than recommended by LAST

Factory. As you may have guessed, I have a custom built setup that I use for this

process. However, you can simply wet a cotton Texwipe® or any lint free cloth with

the lubricant and apply it to the oxide while rewinding or forwarding the tape very

slowly. By slowly, I mean roughly 5–15 inches per second. You can play the tape as

a convenient way to move it at a constant speed while applying the lubricant

however, I would recommend threading the tape directly from reel-to-reel. If you do

play the tape, I would recommend applying the lubricant on the incoming side of the

tape before it comes in contact with the heads and I would also recommend

covering the heads with Teflon® tape. Teflon tape is very slippery and will protect

the valuable oxide, plus it avoids unnecessary head wear. If it at all possible, avoid

any other stationary objects such as incoming or outgoing idlers or guides.

This is why I suggest threading the directly from one reel to the other.

While applying the lubricant, Use an eye dropper to keep the cloth wet. The kit from

Last Factory usually comes with applicators so, try them to see if they work for you.

Stop as often as necessary to re-fold the cloth and wet it again. You can back up

the tape some, if needed. No harm will be done if the lubricant is applied over a

section that has already been done. The lubricant does evaporate quickly from the

oxide however, I have not encountered any adverse effects from the layers winding

onto the take-up reel before the lubricant has evaporated completely. While I don’t

drench the tape, I do make sure that the coverage is such that the oxide gets wet.

Because I’m coming in direct contact with the fluid, I wear rubber gloves or

disposable food handling gloves for the application process even though I have

been personally assured by the manufacturer that all of their products are safe to

handle. I’ve used Last Factory’s tape preservative on all types of polyester base

audio tape and acetate base magnetic film as well with good results. I do not

recommend lubricating acetate base audio tape although the manufacturer says it’s

OK. Magnetic film (16MM, 35MM etc.) is different in that the acetate base is several

times thicker than audio tape and so is the oxide coating. LAST Factory claims that

treating magnetic media with their lubricant will increase shelf life. I have only

anecdotal evidence to support this, but I can say that I’ve noticed no adverse

effects on my own tapes after about twenty years of storage.

I have recently added an article dedicated to lubricating audio tape.

Baking Polyester Tape

First, I will only bake a tape as a last resort when no other restoration method is

applicable. I use a food dehydrator. It can be that simple. The dehydrator I use

regulates the temperature by manually adjusting the air flow through the unit. It’s a

simple dehydrator which has no temperature gauge. To make sure that things are

at the correct temperature, I use a very accurate digital thermometer with a long

probe that allows me to monitor the temperature at the tape reel.

I typically use a constant temperature of 118 - 120 degrees Fahrenheit (48 - 49

degrees Celsius) or less. You can be within 5 degrees or so and be fine. At 120

degrees Fahrenheit, the baking time will be 8 to 12 hours for ¼” tape. If you want to

be safe, operate on the low side and bake the tape longer. I’ve baked tapes at

around 115 degrees Fahrenheit for 24- 48 hours and longer with great results.

Avoid temperatures exceeding 130 degrees Fahrenheit (54.5 degrees Celsius)

because you will risk damaging the tape.

I have also written an article dedicated to baking audio tape.

Important:

Know that not all brands or types of polyester audio tape will respond to the baking

process. Make absolutely sure of the type of tape you have. Research it well before

trying anything.

Whatever type or brand of oven you use, it has to be temperature stable within a

few degrees. Because the air temperature and humidity are ever changing, (time of

day, time of year), I run my dehydrator for several hours while monitoring the

temperature at the area where the tape is to be placed before I begin the process

of baking any tapes.

Any oven used for the purpose of baking magnetic tape should not be used for

anything else. It should go without saying that a food dehydrator should not be

used both for food and magnetic tape.

Always seek advice from a professional before trying anything for the first time.

Transferring Reel-to-Reel Audio Tapes

I’m not sure how to describe a process that takes years of experience. Getting the

best possible transfer is much more complicated than just threading up the tape

and pressing the Play button. I would start by doing lots of due diligence (a legal

term). Do the research and learn everything that you can. There are some articles

on this site that will help.

Audio Cassettes

While there are several formats, the Compact Cassette is the most common.

The word ‘cassette’ is a French word meaning: “little box.” The technology was

originally designed for dictation machines and the format was monaural which,

could be recorded in both directions. Compact cassettes became a consumer

format in the early 1970’s and the format was stereo that could also be recorded in

both directions. The tape itself is poorly supported which, in most machines, causes

skewing that leads to azimuth and wow and flutter problems. Many cassette

machines run at slightly different speeds making for compatibility problems. You will

find that many audio cassettes have been recorded with peaks well above the

normal recording levels than the tape was designed for. When it comes to

transferring cassettes that were recorded in mono or stereo, the main problem is

azimuth. I prefer to use a dual capstan machine for the format. A dual capstan

machine tends to hold the tape steadier. Some Nakamichi cassette decks have pad

lifters which, can also be a bonus. Here is a guide to transferring cassettes which,

is a downloadable PDF file: https://tinyurl.com/2p86v7wb

The only thing that I would add to the guide is to exercise all audio tapes. Fast-

forward and rewind all cassette based media before transferring. Learn what a

cassette in good condition sounds like while fast-forwarding and rewinding and

listen while exercising each one.

For reel-to-reel tapes, use the shuttle mode if your tape deck has one. Some tape

decks make tape head or lifter contact in shuttle mode which, can be a bad thing.

Otherwise, I recommend threading the tape directly from one reel to another,

using one hand (protected) to control the speed.

Storing Audio Tape

All of your audio tapes, records, and optical media should be stored vertically (on

edge). Store all of your media in a cool dry place that is away from excessive heat

or moisture. So, how many times have you read that on the label of a flour box?

Well, it’s true. Keep all of your media in an area where the temperature and

humidity are the most stable. Large fluctuations in either will accelerate

deterioration. Check with your local librarian for information on this subject.

Archivists recommend an average temperature of less than 50 degrees Fahrenheit

(10 degrees Celsius) and 30 - 40% relative humidity or less.

Those ‘ideal’ conditions may be difficult to attain in the average home,

but maintaining room temperature at 30 - 40% relative humidity (or less)

is possible. This likely leaves out the basement and attic unless one or both have

been built to maintain a stable temperature and humidity year round. Storing your

magnetic media on the highest shelf in a centrally located closet will probably be

the most stable environment in the average home. I live in the desert mountains on

the West Coast of the US, where a closet shelf works well and the audio tapes

have faired well over the years.

Analog tape recording has seen a niche resurgence by artists who prefer the sonic

characteristics of analog tape. During the heyday of analog recording, there were a

dozen or more manufacturers of tape stock and as many manufacturers of

recorders. Today there are only a couple of manufacturers of analog tape left and

nobody, that I know of, is making new reel-to-reel recorders.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention again that if you have some old family

recordings and you are the least bit unsure about them, please consult a

professional before doing anything.

You may have only one chance to play them.

My advice is always free and their is a ‘Contact Me’ button at the top of all pages.

Return to TOP of page

© Corey Bailey Audio Engineering

DO IT YOURSELF?

ANALOG TAPE

BAKING AUDIO TAPE

LUBRICATING AUDIO TAPE

MOISTURIZING ACETATE

TAPE

RECORDS (DISCS)

RECORD CLEANING

REPAIRING A BROKEN 78

FLATTENING A RECORD

ARTICLES

A Little About Sound

Baileyzone

Bit Depth

Conductive Paint

Mold

Optimizing your PC

Packing Records for Shipment

People I have Known

Playing Records Wet

Playing a Wire Recording

Sample Frequency

Saving Your Family Video

SSD’s

The Alley

The Internet

The Ken Slater Tapes

Time Charts

Transfer Stories

Tubes vs Transistors

What Type of Wire?

Your Digital Data is at Risk

FIG 1.

Acetate Tape

FIG 2.

Polyester Tape

FIG. 3: 2 Track format

FIG. 4: 1/4 Track format

The picture to the Left,

(Fig 4) is that of a quarter-

track stereo format to

show the difference in

track width.